Dickens and the Christmas Pudding

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

Mrs. Cratchit left the room alone—too nervous to bear witnesses—to take the pudding up and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose—a supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Unlike this pudding, which was made in a mold, Mrs. Cratchit’s was round from being boiled in a cloth. Dickens emphasizes their poverty by having it boiled in a laundry tub rather than a large cook pot.

This image of the flaming Christmas pudding in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol has no relationship in the average American’s mind to pudding as we know it. Most Americans think of pudding in terms of the single-serving snacks bought at the grocery store or the instant dessert whipped up from boxes of pudding powder and milk. A very few have made pudding from scratch. In England pudding has a long history as both a sweet and savory dish. The Cratchit’s pudding is an English Christmas pudding of a type once made in America but largely abandoned over a century ago.

In culinary terms, a pudding is a mixture of foods cooked in a container such as an animal skin or organ, a cloth, a pastry or a dish. The English pudding has connections to sausage, dumplings, flans, custards crème brulee, and zabaglione. According to several sources, the term pudding likely comes from the Latin botellus via the French boudin, both meaning sausage. It could also be derived from the Germanic pud meaning to swell or puddek meaning lump.

Black pudding, or blood sausage, dates back at least to the Greeks and Romans. It features grains like oatmeal and breadcrumbs, herbs, and suet mixed with blood, usually from a freshly slaughtered pig or sheep, and boiled in intestines or a stomach lining. When made without the blood, it was a white pudding (like Haggis). The Romans likely brought this dish to England during their occupation, and it probably continued to be made after they left. At a time when cooks often had only one pot, a pudding was convenient since it could be boiled in liquid with other foods. After the 16th century, English cooks were more likely to have access to an oven and could bake or steam puddings. In the early 17th century, they started to use pudding cloths, rather than animal entrails, as the container. Some wrapped the filling in pastry before boiling or steaming it. This is where the dish became more like what we would call a dumpling or pie.

Here is a recipe for a black pudding of 1670:

Black Pudding: To make fine Black Puddings

Take the Blood of a Hog, and strain it, and let it stand to settle, putting in a little Salt while it is warm, then pour off the water on the top of the Blood, and put so much Oatmeal as you think fit, let it stand all night, then put in eight Eggs beaten very well, as much Cream as you think fit, one Nutmeg or more grated, some Pennyroyal and other Herbs shred small, good store of Beef Sewet shred very small, and a little more Salt, mix these very well together. Ensure your Guts very well scoured, and scraped with the back of a Knife, fill them but not too full, then when you have tyed them fast, wash them in fair water, and let your water boil when they go in; then boil them half an hour, then stir them with the handle of a Ladle and take them up and lay them upon clean straw, and prick them with a Needle, and when they are a little cool put them into the boiling water again, and boil them till they are enough.

From The Queen Like Closet, Hannah Woolley, 1670

The pudding had become a staple of the English diet by the 17th century. There were sweet puddings, bread puddings, and savory puddings. They were made in skins, cloths and pastries. They were boiled, steamed or baked in an oven. A wide variety of puddings were listed in Hannah Glasse’s 1747 The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy, including ones made with apples, oranges, almonds, carrots, vermicelli, spinach, peas, marrow, liver and pork.

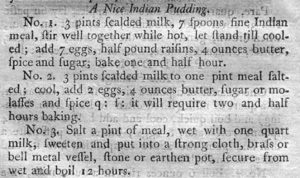

English colonists brought the pudding with them when they settled the Americas. As with many other dishes, colonists had to adapt their recipes to the foods available in the New World. In the earliest years, milk, eggs, and wheat were not plentiful, but Indian corn or maize was. By substituting corn meal for the traditional wheat flour used in some puddings, New Englanders developed the uniquely American dish, Indian pudding. It blended the European pudding tradition with the New World corn and molasses. The first American cookbook, the 1796 American Cookery by Amelia Simmons, includes three recipes for Indian pudding.

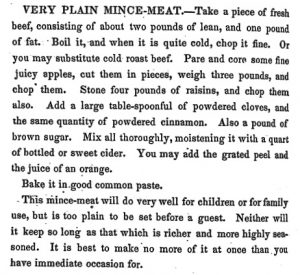

By this time, Americans seem to have parted with meat-based puddings, at least in cookbooks. Simmons and other early American cookbook writers include a variety of puddings, but none are really the savory puddings of British tradition. A few don’t contain sugar, but usually have fruit or molasses in them, or the cook is instructed to serve the pudding with a sweet sauce. By Dickens’ time, English cooks wrapped their meat-based puddings in pastry before boiling or steaming them. In American kitchens, similar fillings were put into pies. Sarah Josepha Hale’s 1841 The Good Housekeeper includes recipes for mince pies and chicken pies, but no savory puddings. The only cookbook I found that contained one was Eliza Leslie’s 1840 Directions for Cookery, which has a recipe for a liver pudding, which we would consider a liver sausage. She also has pies of mincemeat, pork, ham, and pigeon.

Even in Britain, the preference shifted over time to sweet puddings. In the 1852 book What Shall We Have For Dinner, Dickens’ wife Catherine published a series of dinner menus for two to twenty people. Although she only gave the names of the dishes, she included a number of puddings. The only one which is clearly a savory pudding is Rump Steak Pudding, served with oysters and kidneys.

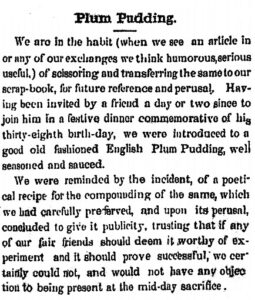

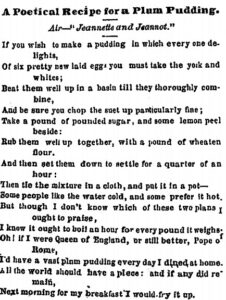

With some exceptions, pudding in England today means dessert. In fact, the term “pudding” is a general word for desserts among the English. The traditional dessert at Christmas time is still a pudding, usually a plum pudding. It seems to have the same connotation among some modern English people as the holiday fruitcake among Americans—traditional but unloved. Although the plum pudding is mentioned in the Geneva newspapers and included in American cookbooks, it does not seem to have been nearly as popular as in Britain. Most mentions of the pudding in the newspaper are in humorous stories involving the dish or histories of Christmas traditions. This piece from the 1858 Geneva Gazette indicates that plum pudding was not a dish often eaten or prepared locally:

- Based on this editor’s account the plum pudding was not commonly eaten in Geneva in 1858.

- A plum pudding recipe for a lady to make.

Perhaps a Dickensian Christmas pudding is something to try for your holiday dinner this year? If so, you can find plenty of recipes on the Internet to help you along. Here is one written in American measurements that might get you started on your own flaming cannonball!

Join the Historical Society and Breadcrumbs Productions on December 3 for “A Christmas Carol: Retold” at Rose Hill Mansion. We all know the story but does the story know us? Performances are at 6 pm and 8 pm. Tickets are $20 per person. Space is limited and reservations are required. Call 315-789-5151 for tickets or purchase online at brownpapertickets.com. This is a show you’ll not want to miss!

Sources

Acton, Eliza. Modern Cookery for Private Families, 1845.

Clutterbuck, Lady Maria (Catherine Dickens). What Shall We Have For Dinner, 1852.

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy, 1747.

Hale, Sarah Josepha . The Good Housekeeper, 1841.

Leslie, Eliza. Directions for Cookery, 1840.

Simmons, Amelia. American Cookery, 1796.

Woolley, Hannah. The Queen Like Closet.

Ysewijn, Regula. Pride and Pudding: The History of British Puddings, Savoury and Sweet, 2016.

I’m in the US and used to make the family plum pudding from a recipe — no one knows how old — from my Scottish relatives on the isle of Jura or maybe earlier from the northwest: Lewis or Harris. I quit making it a few years back because so few in my family loved it like I did. Then I got gluten intolerant, which sealed its fate as a mere merry memory.

Hi Amy,

Would you like to share your recipe?

Since it was passed down from your relatives in Scotland maybe it is quite old. It might be fun and interesting for me to try making it. Also, my relatives are from Scotland, but unfortunately no one passed down any family recipes.

Best wishes for a Happy New Year.